Governing Digital Public Infrastructure

Stay up-to-date on trends shaping the future of governance.

What is Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) and why is it tricky to govern well?

Bricks vs clicks: physical and digital infrastructure

I have spent a good part of my career on the design and implementation of retail payment systems around the world. Accelerated by the rapid spread of mobile phones, digital payment systems are now being used by a critical mass of people in many countries. Although the sums being transferred are low relative to large value payment systems, these digital systems are increasingly recognized as ‘prominent’ or ‘system-wide.’ Their large reach across society has made them a leading example of what is now called digital public infrastructure (DPI). This new name is both a recognition of the growing reality of their importance, as well as a call to action to build more and build better. So what is DPI and how does it differ from other forms of infrastructure?

According to Marte Nordhaug and Kevin O’Neill in their July 2021 blog, DPI comprises “systems which allow data to flow seamlessly while accomplishing basic but widely useful functions at a societal scale”. They argue that DPI should enable a rapid, more effective response to crises, and can also provide the foundation for more inclusive digital economic development. As a result, development financiers are now actively considering new ways to promote the building of DPI.

Development financiers have long recognized the importance of physical infrastructure for development. Elaborate public-private mechanisms have been designed to attract private financing because state financing alone is inadequate. However, according to projections of the Global Infrastructure Hub, a G20 initiative which tracks these trends, the gap is growing between the financing needed to bring physical infrastructure up to SDG standards and the likely funding available. In an October 2020 blog, the Global Infrastructure Hub suggests that the reasons for this shortfall have a lot to do with a poor public governance environment in developing countries.

The limits of private governance of DPI

In this context of generally weak public governance, how should the emerging new category of digital infrastructure be governed? The answer to this question will affect both the ability to attract funding and whether it can achieve defined social purposes. Can DPI escape the governance problems which have plagued many large physical infrastructure projects?

The default approach to governance of DPI so far has been to leave it to privately owned infrastructure operators. This is true for some of the most globally important DPIs today, like Google search and Facebook’s social media platforms. These are governed primarily through corporate governance of these public companies. Accountable ultimately only to its founder who still controls 58% of voting shares, Facebook itself functions like an authoritarian nation state as Adrianne Le France writes in a September 27 2021 article in The Atlantic. Under public pressure, Facebook’s governance is in fact evolving. Facebook appointed an Oversight Board which began work in 2020 to arbitrate content policy on its platforms. But this move alone cannot be the final word in the governance of DPI of this sort.

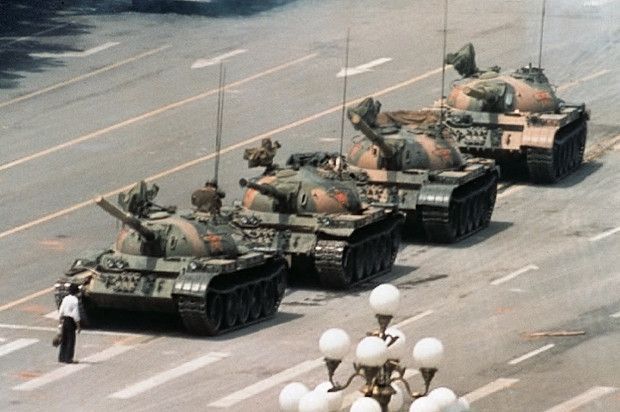

Tech giants like Facebook and Google have such lucrative core business models that not only do they provide their widely used digital services for free but they can also spend considerable sums on the rollout of the physical infrastructure for digital connectivity in developing countries. However, the model of privately owned, operated and governed digital infrastructure is hitting its limits. The apparent alignment of interests between big tech and the governments which used to welcome their taking care of the problem of digital inclusion at little or no cost to the state has broken down. Only in authoritarian states so far has there been the will and the power so far to regulate tech giants closely, or else to provide DPI directly.

Governance of the digital space in general, and especially of DPI, is indeed one of the central questions of our time. It needs focus, resources and urgency. Tristan Harris, the founder of the Center for Humane Technology which was behind the Emmy winning 2020 documentary The Social Dilemma has called for a ‘Manhattan project’ on digital governance In a September 2021 edition of the Center’s podcast Your Undivided Attention.

An alternative approach: Digital Public Goods

The ‘P’ for ‘public’ in ‘DPI’ has referred to public in the sense of population scale usage, rather than public ownership of infrastructure, as the Facebook example shows. But what if DPI could be rolled out on the foundation of non-proprietary assets? This could change both the cost basis and the governance model.

This is the essence of an emerging approach to the rollout of DPI which relies on deploying digital public goods (DPGs). DPGs are open-source approaches to software, data, AI, standards and content. In the tighter form of the definition espoused in the UN 2020 Roadmap for Digital Cooperation, these open approaches must also:

1. adhere to privacy and other applicable best practices,

2. do no harm and

3. are of high relevance for attainment of the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

DPGs are not necessarily free, but the principle of ‘openness’ of access applied across a spectrum of licensing options removes the thick wedge of monopoly rents accruing from proprietary ownership and reduces the risk of lock-in to proprietary solutions. To advocate for the widespread use of DPGs for development purposes, a group of interested organizations led by a bilateral donor (Noraid) and a UN agency (UNICEF) set up the Digital Public Goods Alliance (DPGA) in 2019. DPGA has operationalized a standard for defining a DPG and maintains a registry of qualifying DPGs.

Reliance on DPGs to build DPI may reduce the total costs of infrastructure deployment although it does not eliminate financing challenges: in fact, DPGs may require considerable investment upfront to create, test and propagate the approaches to the level where they are robust and can be relied upon. This is especially true in societally sensitive sectors such as identity provision and management. Because their open source nature dilutes potential returns relative to proprietary options, DPGs are less likely to be able to attract commercial finance. This places more pressure on concessional pools of finance.

DPGs also don’t eliminate the fundamental problem of weak governance in many developing societies but they change it: they shift the locus of control away from governments negotiating with proprietary vendors towards the standard setting bodies which guide, vet and control the open solutions. The governance of open source solutions differs widely: from relatively authoritarian around charismatic founders (think Linux or Ethereum) to more community-based forms.

Open-source foundations

provide the legal homes and oversight for an increasing range of open software. Some of the best known of these include

Apache Software Foundation

and

Mozilla Foundation.

To entrench their independence from private interests, these foundations usually take the legal form of nonprofit companies which have a corporate board of directors appointed to represent wider stakeholders and a technical board appointed to oversee technical standards. The

Mojaloop Foundation formed in 2020 to guide the development of an open-source payments ecosystem is one of the most recent.

Governing the great ‘Opens’ of our time

Mojaloop is an example of the wider trend towards Open Payments and Open Finance more generally which has gathered momentum in many parts of the world in ways which have the potential to transform retail finance thoroughly. The infrastructure supporting these latest ‘opens’ are also part of DPI: they perform the complex tasks of setting and maintaining standards, publishing software APIs and enforcing data protection norms. Building and operating this infrastructure requires a new breed of adequately resourced entities, the specialized governance of which must be able to balance conflicting interests while achieving a defined public purpose.

Governing DPI is no easy task. But it is an essential task if the benefits of DPI are to be realized in the form of meaningful digital inclusion and the achievement of SDGs. That’s why at Integral, we will watch closely what is happening in this emergent area; and why we have an active interest in supporting better governance outcomes especially of DPIs.

I personally don’t think that this will require a single ‘Manhattan project’ as Tristan Harris argues for digital governance more generally: rather it needs an active learning approach to observe closely the evolving governance of the many different forms of DPG and DPI already active around the world today. It must allow for the diversity of contexts and challenges while exploring and supporting common emergent themes. It also needs to experiment with new digital organizational forms--perhaps DPGs will be housed in Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) in the future. In this mix of experiences, it is more likely that strong and appropriate governance can be identified and then cultivated for DPI in future.

At Integral, we provide ESG Consulting advice, evaluation, facilitation, mentoring and coaching services to develop governance systems that fit your organization’s purpose and stage of growth. To explore further how we can help you,

read about our services, or

set up a free consultation.

S H A R E