How to Build Effective Digital Public Infrastructures

Stay up-to-date on trends shaping the future of governance.

Reducing the Risk of Ineffective Digital Public Infrastructures

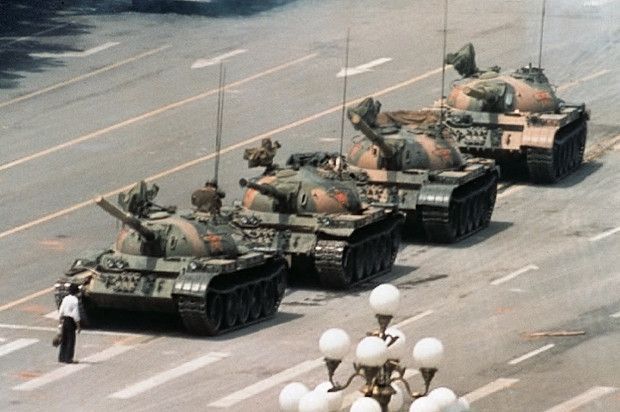

There are many risks associated with the rollout of Digital Public Infrastructures (DPIs). They can open the backdoor for governments to surveil and control their citizens. They can even fall into the hands of malicious actors and be used against the people they were designed to serve. Understandably, in the growing movement propagating DPIs, many people wish to reduce risks like these. However, in my view, a risk with less severity but perhaps higher probability is that many DPIs are simply not effective–meaning that they fail to fulfill the purpose set out by their creators or funders. As a result, they may become expensive ‘white elephant’ projects, like their counterparts in the world of physical infrastructure: “bridges to nowhere” or roads and dams built without real consideration of their use, but which are expensive to maintain. A world full of ‘white elephant’ DPIs may not seem as dark as other digital dystopias, but if the DPIs are indeed that important, the absence of well functioning DPIs carries costs. Of course, effective DPIs do not guarantee utopia either; but having more effective DPIs which achieve their purpose seems like a reasonable and attainable goal.

Governance challenges for DPIs

To achieve this goal, the question then becomes: how best to design, build and operate effective DPIs? I am convinced that a large part of the answer is by building sound governance structures which take into account both the specific and generic challenges faced by new DPIs.

First, the

specific challenges of DPIs. The envisaged large scale of deployment of most DPIs leads to heightened degrees of caution and oversight from the start in ways which typically do not constrain private startups. At the same time, DPIs often need the nimbleness to compete for take up against indirect competitors at least–for example, instant retail payment systems are a fast-growing category of DPI which rely on customers choosing to use them, rather than other available means of payment. In addition, many DPIs are built and managed as public-private partnerships. The ‘partnerships’ may take different forms: from build-own-operate contracts to service agreements; or indeed, using software provided by private open-source foundations. This aspect adds an additional layer of complexity on top of standard corporate governance.

Underlying these distinctive challenges are more generic challenges. New DPIs are in many respects more like private tech startups facing similar challenges of achieving ‘product-solution-fit’ and then managing scaleup. These types of challenges need also to be recognized in designing DPI governance arrangements because DPIs are not ‘born adult’: they often have to walk a long path before they can achieve and also handle significant scale of usage. The design of DPI governance must recognize not only this need for evolution but also support it. This recognition carries several implications. One is that governing early-stage companies requires different skills and experience sets from governing mature entities: in fact, our research among funders and founders of tech companies suggests that it can be counterproductive to appoint non-executive directors with experience in large, established public companies to the boards of startups. Instead, people who may have less board experience but who understand startup challenges may be more valuable to support a startup to the next stage. So too, then, with DPIs: a board weighted towards too much formality from the start may bog down the agility required in the early stages.

Balancing agility with accountability

Of course, too little formality may carry costs too. In a previous Integral article, I have described the situation which developed at the Open Banking Implementation Entity (OBIE), the operator of the open banking infrastructure in the UK. The OBIE was established as a company under a regulatory order which required major British banks to fund its establishment and to participate in it. In line with startup logic, the OBIE operated under a lean governance structure with a dominant single independent Trustee on its small board. Five years after its establishment, an independent investigation in response to whistleblower complaints found that the OBIE had been effective in its core task of promoting open banking, yet had failed in some basic elements of corporate governance relating to its treatment of staff and contractors; and failure to remedy what was described as a ‘toxic working culture’. So, a delicate balancing act is required to achieve success without ‘breaking things’; and maintaining this balance is the core task of governance.

Two forms of DPI governance

In the case of many DPIs, as indeed with the OBIE, there will usually be two forms of governance:

- External governance from a regulatory authority which oversees and may license a DPI: this may include powers to appoint directors and to intervene in defined circumstances; these powers may derive from a general regulation or from a specific order issued under general authority, as in the case of OBIE.

- Internal governance

which takes the form of a decision making body established directly to oversee the work of the DPI; this body may take the form of a board of directors if the entity is a company, in which case the nature of governance is shaped not only by domestic corporate law but also by codes and guidance which pertain to corporate directors. These codes are typically designed to apply to public companies, usually meaning those listed on a stock exchange. While most DPIs are unlikely ever to list equity, they nonetheless function as public companies in terms of the levels of scrutiny and accountability expected of them. While small and unlisted, OBIE faced expectations that conventional norms and standards would apply to its activities.

Examples of blending both with payment systems

These two complementary forms of governance need to be carefully blended to provide the right mix for DPI success. To see how to do this, we can draw some insights from the world of payment systems. Payment systems are one of the earliest categories of DPI, dating back thirty or forty years in many places. Following the Covid pandemic, usage has soared in many places and new systems have been established. Payment systems vary in their ownership–many are privately owned or controlled by their participating members even though they may operate as not-for-profit companies, while some are owned and operated by central banks.

A recent World Bank research paper has looked in detail at the

Governance of Retail Payment Systems. Several aspects stand out. First, most countries now have an external regulatory framework which gives oversight powers to a payment system supervisor, usually the central bank. The external oversight usually includes some consideration not only of risks, as is common in financial sector regulation, but also of the efficiency and effectiveness of the national payment system as a whole. However, many payment systems also have internal governance through board of directors; and the ways those boards are appointed and function has an important influence on their effectiveness.

More successful payment systems have been able to build the agility to evolve over time, while ossified governance arrangements tends to lead to stagnation or even decline.

Payment system governance recognizes the

key principle of proportionality: that is, that the intensity and scope of governance should be in proportion to the risks which it seeks to ameliorate. Proportionality is recognized even in international standards for payment systems: the

Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMI) set by the international payments standard setting body housed at the BIS, defines standards for systemically important payment systems. Non-systemically important payment systems may fall into other categories, such as prominent retail payment systems which are widely used for low value transactions and ‘other’ systems. In the latter case, the need for external oversight may be quite limited as long as the internal governance is strong.

Application to DPIs

For the wider world of DPIs, the experiences of payment systems provide a few pointers to success: first, a blend of external and internal governance is required; second, proportionality must apply to both forms of governance; and third, some DPIs may be so significant that the equivalent of international standards like PFMI should apply to their governance and operations. Of course there is not yet a standard setting body for DPI in general equivalent to CPMI for payments. Finally, fourth, the mixed successes of new payment systems highlighted in a recent study of instant payment systems in twelve countries raise a range of internal governance questions and considerations. Establishing sound and evolving internal governance requires intentional effort. While there are many places offering training focused on corporate directors in public companies, where are the forms of training optimized for the specific challenges of DPIs highlighted earlier, such as their public-private nature?

Finally, even in its quite evolved form in payments systems, external governance has its limits. For one thing, it is often more focused on risks than on opportunities since the nature of financial regulators is to consider risk. Even internal governance can easily become preoccupied with risks, leading to the loss of the agility required to identify and take advantage of opportunities. To balance the consideration of risks and opportunities, DPIs need to keep up a focus on achieving their purpose, which involves both.

A role for Public Protectors of DPI

Especially if there is no sectoral regulator in place or if that regulator lacks capacity, then defining the role of a public protector of DPI may help. William Frater and I have previously proposed that a public protector role be identified for important DPIs. This role would be played by an individual with the necessary skills and experience, and may be implemented through the contractual arrangements of setting up a DPI without having to wait for new regulation. The protector, funded by a specific budget provided by the DPI, would be independent of internal governance. It would have the powers to investigate, and if a DPI is failing to achieve its stated public purpose, it could make recommendations to external governance or intervene directly in internal governance. To be clear, this role would not usurp the role of specific sectoral regulators, such as Data Commissioners or indeed payment system regulators. But for designated classes of DPI, it could help to improve the likelihood of DPI effectiveness by creating an empowered point of accountability focused on the question of purpose and effectiveness.

Think of DPI Protectors as game wardens, if you like, whose job is to ensure more working elephants than white elephants in the world of DPI. And of course, Protectors would also have powers to deal with ‘rogue elephants’ when they arise in dystopian scenarios of rampant abuse of privacy or other citizen rights.

At Integral, we provide ESG Consulting advice, evaluation, facilitation, mentoring and coaching services to develop governance systems that fit your organization’s purpose and stage of growth. To explore further how we can help you,

read about our services, or

set up a free consultation.

S H A R E